Why Everything is Like the Bar Scene in Good Will Hunting

I was having dinner with a friend the other day, who mentioned that one of his great fears was that he was just a stochastic parrot, recombining and recapitulating the sources he reads. For what it’s worth, I think he’s great, but it’s definitely something I’ve worried about in the past; is anything I say or write that original? Perhaps even the ideas I have for our company aren’t all that; what do I know, that nobody else does? What is there of originality in anything I produce?

I think this is a great reason to be bullish on language models; because even if they’re stochastic parrots, that’s basically all the rest of us are doing anyway. Somehow, that stochastic parroting produces academia and white collar work, and then downstream of that you get the greatest system of wealth creation in the history of humanity. So much for stochastic parrots.

One of my other friends likes to say, ‘Felix, not everything is like the bar scene in Good Will Hunting’. I respectfully disagree. It’s one of the great pieces of culture. If you’ll forgive me, I’ll talk a little about why I like it, and then get back to the bigger point I’m making.

First, I just love the quiz that happens in the scene. Will’s put under pressure - challenged to come up with a response - and manages it. “Wood - Wood drastically underestimates… You got that from Vickers? Yeah, I read that too.” That kind of thing really motivates me - coming up with the goods, when someone drastically underestimates you, dragging the information from the depths of the post-frontal cortex or whatever into the working memory, writhing and twisting to find the glistening scrolls that answer the question you were posed. My University Challenge team never made it on to TV (sadly, it works more like a talent show than the FA Cup), but I think I enjoyed that game more than any other I’ve tried.

Will’s innocence is also appealing. He didn’t set this one up - he was just there to back up his friend. And he wasn’t even bold enough to go approach Skylar - he didn’t even realise he should. His semi-autistic naivety, his refusal to play the game, is particularly appealing as an ideal to those of us who do sometimes have to play the game. My job used involve going to conferences to try to sell software to people; I always wanted more meetings, more interactions, and a sure-fire way to generate them was to hang around the meeting points and grab people as they waited for their interlocutor. It becomes easy, after a while: “You’re also waiting? For a meeting? Yeah, me too haha, I hope I’m in the right place. Wait, what’s your name? Oh nice, what does your company do? ….”

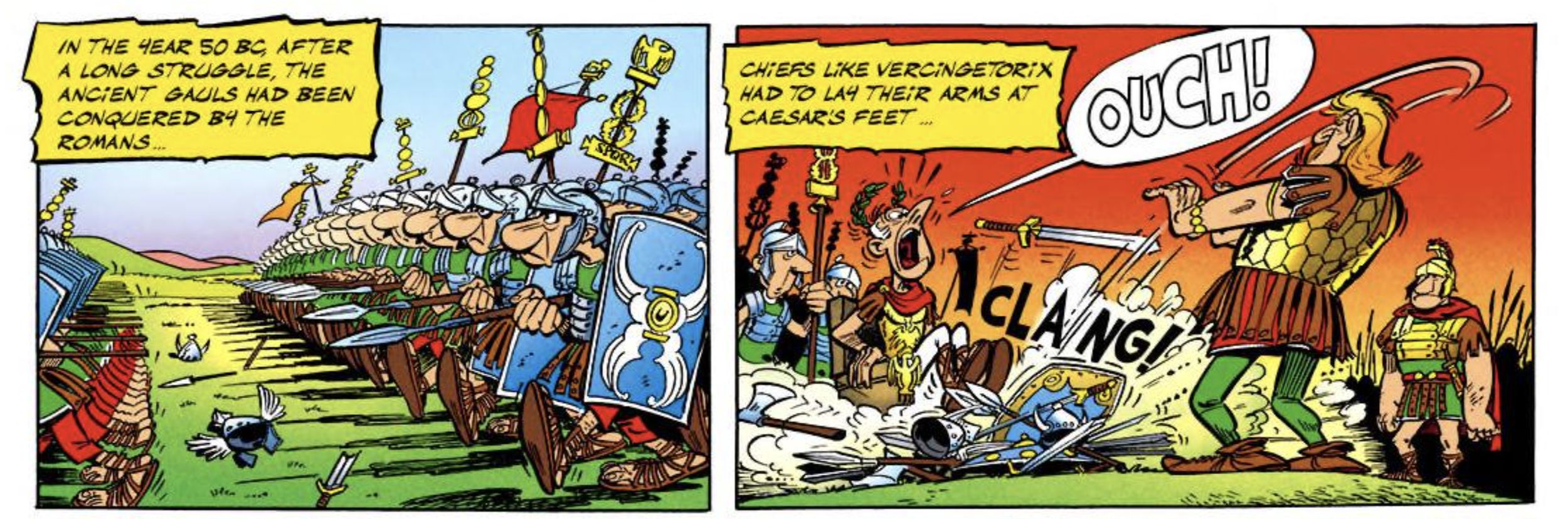

That makes his vicious, barbarian satisfaction all the more appealing. How’d you like them apples! I mean, I have no idea of the aetiology here, but it reminds me of Billy Connolly talking about the phrase “fuck off”: “everybody feels what it means, nobody can write it down.” It’s like the defeated king Vercingetorix, at the start of Asterix the Gaul, hurling his arms at Caesar’s feet. I live for those moments too.

And as a recovering intellectual historian, I love the cut and thrust of their debate. A wag once said that the study of history was invented by J.R. Seeley at Cambridge as “a good subject for allowing undergraduates to exercise some sort of intelligence on an intelligible and indeed intelligent subject matter.”; and that’s exactly what Will does with the baddie. The back and forth, my citation versus yours, the nuance your argument failed to consider and the reframing I offer instead, your misreading of the original source and the extra context my detail provides; perspiration and inspiration combined to produce erudition and scholarship, the Quellenforschung of the undergraduate. It’s just what it’s all about. If you know, you know, and, as the sixteenth-century Aragonese coronation oath used to say, if not, not.

But the scene isn’t just fun - it raises an important point. To what extent are we all just reading some obscure passage to impress some girl? And am I just contending this because I’m a first year grad student? Because if I’m going to be serving fries at a drive-through (metaphorically, perhaps), do I even get to be original here? Later in the film, we get an answer: Robin Williams says that originality comes from lived experience, from smelling what it’s like in the Sistine Chapel and loving your wife through cancer. So, tough luck book-readers - get married and get on that plane, because that’s the only way to really learn something about the world.

But my gosh, so much of what we know about the world is just a cloth woven on the loom of our reading; warp and weft, other people’s words. I can’t even explain this point without going back to Edward Said, who in turn drew heavily on Foucault, who drew on… But seriously, after I read this passage I went back to my tutor and asked him, how could anyone even hope to understand the world without thinking about dialectics? Perhaps I was an impressionistic 20-year old, but I think there’s a lot of explanatory power there.

Said’s point is that Europeans who came to the Orient did not come with open eyes and a tabula rasa; they came filled with ideas from their reading. Orientalists like (random example, because it’s a funny name) Schlegel were much less interested in the living, contemporary Orient, than the one they imagined:

“First, there is disappointment that the modern Orient is not at all like the texts. Here is Gérard de Nerval writing to Théophile Gautier at the end of August 1843:

'I have already lost , Kingdom after Kingdom, province after province, the more beautiful half of the universe, and soon I will know of no place in which I can find a refuge for my dreams; but it is Egypt that I most regret having driven out of my imagination, now that I have sadly placed it in my memory.'

This is by the author of a great Voyage en Orient. Nerval's lament is a common topic of Romanticism (the betrayed dream).”

As Said put it, for Western travellers, the “Orient is not the Orient as it is, but the Orient as it has been Orientalized.” He interprets all this through what he calls a textual attitude; the idea that the “swarming, unpredictable and problematic mess in which human beings live can be understood on the basis of what books - texts - say”. Here’s the (rather long, but genuinely really powerful) passage in which Said explains his ideas:

“Two situations favor a textual attitude. One is when a human being confronts at close quarters something relatively unknown and threatening and previously distant. In such a case one has recourse not only to what in one's previous experience the novelty resembles but also to what one has read about it. Travel books or guide books are about as ''natural" a kind of text, as logical in their composition and in their use, as any book one can think of, precisely because of this **human tendency to fall back on a text** when the uncertainties of travel in strange parts seem to threaten one's equanimity. Many travelers find themselves saying of an experience in a new country that it wasn't what they expected, meaning that it wasn't what a book said it would be. And of course many writers of travel books or guidebooks compose them in order to say that a country is like this, or better, that it is colorful, expensive, interesting, and so forth. The idea in either case is that people, places, and experiences can always be described by a book, so much so that the book (or text) acquires a greater authority, and use, even than the actuality it describes. The comedy of Fabrice del Dongo's search for the battle of Waterloo is not so much that he fails to find the battle, but that he looks for it as something texts have told him about.

A second situation favoring the textual attitude is the appearance of success. If one reads a book claiming that lions are fierce and then encounters a fierce lion (I simplify, of course), the chances are that one will be encouraged to read more books by that same author, and believe them. But if, in addition, the lion book instructs one how to deal with a fierce lion, and the instructions work perfectly, then not only will the author be greatly believed, he will also be impelled to try his hand at other kinds of written performance.

There is a rather complex dialectic of reinforcement by which the experiences of readers in reality are determined by what they have read, and this in turn influences writers to take up subjects defined in advance by readers' experiences. A book on how to handle a fierce lion might then cause a series of books to be produced on such subjects as the fierceness of lions, the origins of fierceness, and so forth. Similarly, as the focus of the text centers more narrowly on the subject - no longer lions but their fierceness - we might expect that the ways by which it is recommended that a lion's fierceness be handled will actually increase its fierceness, force it to be fierce since that is what it is, and that is what in essence we know or can only know about it. A text purporting to contain knowledge about something actual, and arising out of circumstances similar to the ones I have just described, is not easily dismissed. Expertise is attributed to it. The authority of academics, institutions, and governments can accrue to it, surrounding it with still greater prestige than its practical successes warrant. Most important, such texts can create not only knowledge but also the very reality they appear to describe. In time such knowledge and reality produce a tradition, or what Michel Foucault calls a discourse, whose material presence or weight, not the originality of a given author, is really responsible for the texts produced out of it. This kind of text is composed out of those preexisting units of information deposited by Flaubert in the catalogue of idees recues. In the light of all this, consider Napoleon and de Lesseps. Everything they knew, more or less, about the Orient came from books written in the tradition of Orientalism, placed in its library of idees recues; for them the Orient, like the fierce lion, was something to be encountered and dealt with to a certain extent because the texts made that Orient possible.”

I think an awful lot in, like, modern politics, comes down to whether you believe that “the experiences of readers in reality are determined by what they have read”. But if Foucault is right that discourses have a weight of their own, that transcends their own authors to touch everyone in society, then that gives a lot of credence to the stochastic parrot view of human ideas. Will was right that the baddie got it from Vickers; but he’s no more original, just better at mental gymnastics. Will doesn’t have any thoughts of his own on American economic history; he’s just weirdly good at opening the bonnet to show the grinding oily drive-train of academic research in the humanities at work.

I guess my best answer to all this is to try to achieve a sort of meta-recognition of your own unoriginality, while still persisting in it. If you are a first-year grad student, and you find yourself making the contention of a first-year grad student, for fuck’s sake just stop, not least because language models can probably do it better and faster. But if you’ve taken into account your bounded experience, the determined nature of your reading and the limits to your self-expression, and you still think it’s worth putting on paper, then by all means, go ahead! Maybe that’s too strong a criterion: in general, I think, we have too few people writing down what they think. If the best do lack all conviction, then the worst thing would be to have someone like me putting another obstacle in the way of them getting the word out.

I think it’s a bit like conversation at parties; in my first year after university, we all talked about the same stuff - “are you enjoying your investment banking job? Oh, you went to bed at 3am last night? You’re also thinking of going to play for your old college rugby team next weekend?” Now, everyone’s like “Did you see they got engaged? I can’t believe it, she’s still so young; I’m so over Hinge dates, I just want my friend to introduce me to someone”; soon it’ll be, like, “I’m thinking of buying a house; maybe we’ve had enough of London, we just need more space”; I can just imagine the agonising over whether you should send your kids to private school. All of this is deeply unoriginal - determined entirely by our job, age, social status, location - and yet is it so bad? Maybe we should all just talk and write a bit more, and never mind what Will Hunting would say about it.