Insurance Broking - the War for Talent

This essay starts in London, the deepest and most sophisticated insurance market in the world.

As a general rule of thumb, big companies with complex needs buy their insurance through London brokers and London underwriters. It’s true that the largest brokers and underwriters in the world are not English; Marsh, Aon, and Willis are all American firms, while Swiss Re and Munich Re are pretty self-explanatory. Yet most of these companies have their largest offices within the Square Mile of the City of London. Swiss Re are in the Gherkin, Aon in the Cheesegrater, Willis in their eponymous Lime Street building, and Munich Re just next door. Marsh stand a little apart, watching over the Tower of London to the southeast. At the heart of the London market is Lloyd’s, a morass of steel pipes and lift shafts sandwiched between Lime Street and the perpetually-Christmassy Leadenhall Market. Lloyd’s represents the market’s history, but it’s also very much part of its present - an association of syndicates and brokers, collectively regulated and backed by each other’s capital. Lloyd’s history of reliability, although decidedly spotty in places, explains much of the dominance of the London market.

In this piece, I’m going to sketch an outline of the global insurance brokerages: what they are, and how they came to be. It’s meant to be an illustrative introduction to this sometimes-bewildering industry - but I won’t have everything right. Let me know what I got wrong!

This image is a few years old - since then, several new skyscrapers have sprouted.

In 2022, companies round the world spent £50bn buying insurance from about 70 Lloyd’s syndicates; but Lloyd’s is merely a subset of the whole London market. Risks can also be underwritten by ‘normal’ insurance companies, and the same risk can be shared between syndicates and insurance companies. Lines get blurry: a broker who approaches Talbot Underwriting (syndicate 1183) might just as well approach AIG, who bought Talbot in 2018, and have an office a few hundred yards away on Mark Lane. But even if the broker approached a Talbot underwriter at the desk (or ‘box’) on the ground floor of the Lloyd’s building, that same individual underwriter could write a risk wearing his company or syndicate hat. Some syndicates are independent, and some big insurers (e.g. Allianz) don’t own a syndicate. This flexibility, combined with the global nature of the business, the byzantine complexity of insurance accounting, and the dated management accounting systems employed by all the players, makes it hard to track exactly how much insurance premium passes through the London market as a whole.

It’s also tricky to know which brokers are bringing in the most business; both brokers and underwriters tend to be guarded about exactly how much business they do with individual counterparties. But according to a Lloyd’s executive, US risks make up about 60% of premium in the Lloyd’s market. Of that, 30% is supplied by eight US retail brokers, and 30% by three US wholesale brokers. The distinction between the two is crucial for understanding the structure of the insurance broking industry.

Most businesses, especially SMEs, buy their insurance from someone they know personally. Because it’s low on the list of priorities, but important to get right, the CEOs or CFOs responsible stick with people they trust - brokers that can answer questions, and be relied upon to bail them out in a tough spot. Personalities, not brands, are key. Because of this, the concept that best explains the structure of the insurance broking market is Dunbar’s Number - the idea that any one person can only hold a limited number of personal relationships. So each broker has up to about a hundred relationships - but no more than that. And since the end-customer relationship is owned by an individual broker, then the challenge becomes aggregating brokers, rather than the customers themselves.

Incidentally, this fact about the market breaks many of the most firmly-held assumptions of software investors. Ben Thompson’s famous aggregation theory holds that direct customer relationships are key to the business model of the tech giants, and software companies across the world have tried to follow that model by capturing those customer relationships. But in insurance, customer relationships aren’t owned by any one company - they’re held by individuals. I had lunch with a former professional rugby player who now works at a top brokerage. He’s been told that the key to his growing career will be to build his own book of business - because with those contacts in hand, he could leave the big company and start his own practice, selling his clients back to his old firm and taking a healthy commission. In time, he’ll take a golden handshake, rejoining his old firm and bringing his clients back into the fold. Some of his colleagues have run this playbook two or three times. To a first approximation, insurance broking revenue belongs to individual salespeople rather than the company they work for.

Brokerages can respond to this dynamic in two ways. You can wrap your producing brokers - the ones that hold client relationships - deep within your organisation, facilitating their work, providing perks, handling painful admin, and making any exit difficult. Or you can accept that producers are going to go out on their own, and focus on servicing them as sole traders and small businesses. Global retail brokerages - notably Marsh, Aon, Willis, and AJ Gallagher - follow the first model. Wholesale brokerages - especially AmWINS, CRC, and Ryan Specialty - follow the latter.

The global retailers drum up business across the world: Aon has offices in 123 countries and 138 US cities. Each office aggregates local producing brokers, providing the central services that match their risks to capital across the world. An Aon producing broker in Kuala Lumpur or Kentucky can email an Aon London broker, and ask them to show a difficult risk to London market underwriters. Since technology is so obviously relevant to these businesses, they adopted tech early - much earlier than construction sites and restaurants - and so these giant organisations are saddled with ancient systems and databases, the heirlooms of the first mover. The global retailers have a simple proposition: come work for us, and we’ll give you the platform you need to be successful.

On the other hand, wholesale brokers are happy to enable independent brokers. The independents (there are around 60,000 firms in the US alone) get paid because of their personal relationships with local businesses; they’re client-focused. But that means they’re not focused on their relationship with the insurers who will underwrite the risk. And while a local broker might be able to get away with a handful of underwriter relationships on a simple risk, anything big or weird starts running into the rusting rhododendron of American insurance regulation.

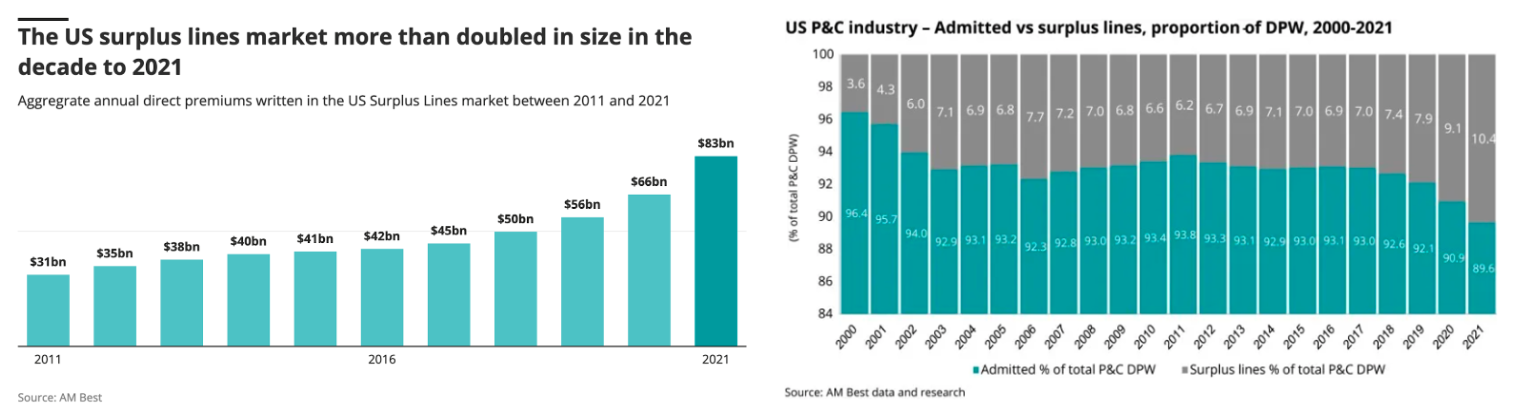

I have it on good authority that the best way to think about the American insurance market is as a giant job creation scheme. Each state has its own insurance regulation, creating a state-wide admitted insurance market; in the admitted market, there are strict rules around rate and form, which limit the kind of insurance policies that can be written. While around 90% of US property and casualty insurance - i.e. everything that isn’t life and health, for both personal and commercial lines - can be written within those rules, the biggest and weirdest risks - seeking freedom of rate and form - flow out of the admitted market into the excess and surplus (E&S) market.

Example: imagine you own a home in Los Angeles. There’s a huge risk of wildfire, quake, and even (as of 2023) hurricanes, and so insurers want to charge you a high percentage of the value of your house as premium. But California state regulation strictly limits the premium that can be charged - and those regulations are a sensitive political football. As such, it might be impossible for any insurer to profitably underwrite California property without exceeding the rate limits set in the state market. In this scenario, your risk would become surplus, because you need to go and seek non-admitted surplus capacity. Alternatively, imagine you own an old tobacco factory in Winston-Salem; if that factory has asbestos in its roof, then it’s possible that no insurer regulated by the state of North Carolina will be willing to underwrite the risk, and you’d need to go and find a specialist insurer with appetite for asbestos and the freedom to write a policy to match.

There’s no particularly good reason for every state to set its own insurance regulations, but that’s the way it’s always been: it creates a huge number of solid middle-class jobs, and it’s not worth it for anyone to try to solve the complexity. Like with guns, health insurance, and self-filed tax returns, the Americans just have to have it their own way. The rule is that if a risk gets declined by more than a handful of state-regulated admitted insurers (the exact number varies between states), then brokers are free to go out-of-state to the thousands of insurance companies in the E&S market. But retail brokers, especially independent agents, are specialists in producing risks from their clients - not in navigating the complexity involved in placing excess and surplus risks. And that’s where the wholesalers come in.

AmWINS, CRC, and Ryan Specialty solve complexity for their retail broker clients, dealing with the most difficult 10% of risks. They compete with each other to solve a two-sided marketplace: 60,000 retailers in the US versus around 1,000 carriers spread across the US, Bermuda, Europe, and of course London . Wholesalers have to keep both sides happy, while also ensuring that their underwriters are creditworthy, and the brokers are staying compliant - for instance, that they’re all buying E&O (errors and omissions) insurance. What’s more, the E&S market has grown steadily over the last few decades, reaching $100bn in 2022 and providing these three wholesalers with headroom to grow.

Dunbar’s number poses a challenge; the regulatory rhododendron complicates it. The global retailers have one answer, and the US wholesalers have another. How did we get here? In a word: rollups.

Henry Marsh and Donald McLennan started an insurance brokerage in Chicago in 1905; over the next century, the business would expand through inorganic growth, steadily acquiring more and more brokers. At their 1962 IPO, Marsh had $52m of revenue; the business now does over $20bn a year.

In 1964, 28-year old Pat Ryan started an insurance broker in Chicago; in 1982, he merged it with another broker to create an entity he called Aon. Just like Marsh, Aon proceeded on a vigorous programme of expansion, buying more brokers wherever possible.

Marsh has remained more or less dominant since their IPO; in 1972, they had $151m in US brokerage revenue, compared with $90m for the second-place Johnson & Higgins. In typical insurance broker fashion, Marsh would acquire Johnson & Higgins in 1997 for $1.8bn.

By 2011, Marsh and Aon each had $5bn of US broking revenue - far ahead of their nearest rival, AJ Gallagher, with $1.7bn. Today, Marsh and its subsidiaries are worth $98bn; Aon is worth $65bn.

But there were been bumps on the road. In particular, a quick glance at Marsh’s long-term stock price reveals a dramatic crash in December 2004.

That crash is down to one man - Eliot Spitzer - who, like Ted Kaczynski, is perhaps better known for other work. Spitzer fined Marsh $850m for “bid-rigging” - colluding with insurers to inflate premiums. Marsh would recover from the fine - but the affair had wider consequences.

In the immediate aftermath, three Marsh execs left to set up a new broker, Integro. The new firm was going to trade with the integrity that Marsh had lacked - but it also had a war-chest of $300m, with which it planned to hire 500 employees by the end of 2006.

In December 2005, Integro bought a Lloyd’s broker, Humphrey Haggas Sutton, but never quite lived up to its initial billing. It would finally reach profitability in 2009, with $65m in revenue. After a series of private equity transactions, Integro now trades in the London market as Tysers (having acquired the venerable London broker shortly before its 200th birthday in 2018).

The history of insurance broking has a certain pattern to it. In 2019, Marsh bought a top London brokerage, Jardine Lloyd Thompson, for $5.6bn.

In the immediate aftermath of the deal Steve McGill, the outgoing Aon Group President - and before that, a 15-year JLT veteran - teamed up with JLT’s founder John Lloyd to set up a new London broker: McGill and Partners. The new firm was going to trade with the white-glove service that Marsh and Aon lacked - but it also had a war-chest of $300m, with which it planned to hire 450 employees and earn $400m/year in revenue by the end of 2023.

Marx once wrote that “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

According to its 2022 accounts, McGill had $111m of revenue (up from $88m in 2021), and 342 employees.

But more significantly, in late 2005 the fallout from the bid-rigging affair forced Marsh and Aon to divest their wholesale arms. Up until this point, Marsh’s wholesaler Crump and Aon’s wholesaler Swett & Crawford had serviced independent retail brokers, along the lines discussed above. But under immense scrutiny, both firms were independently spun out to private equity. Willis, which had $2.3bn of revenue in 2004, saw the way the wind was blowing, and divested their own wholesaler, Stewart Smith. But rather than selling to private equity directly, Willis sold to an existing platform - American Wholesale Insurance Group, or AmWINS. AmWINS since built on that acquisition with many more, steadily becoming one of the largest wholesalers in the US.

During the 1990s, BB&T, a North Carolina financial services company, had been steadily buying up brokers across the Atlantic Coast, and in 2002 they acquired Alabama-based CRC Insurance Services. CRC would serve as the platform for the next twenty years of the rollup, which included the acquisitions of Crump and Swetts in 2012 and 2016 respectively, along with literally hundreds of other bolt-ons.

This story comes full circle. In 2008, Pat Ryan retired from Aon, the broker he had founded 44 years before. Keen for some peace and quiet, the 74-year old spearheaded the Chicago Olympics bid, as well as funding a wing of the Art Institute of Chicago, before deciding that he wasn’t done yet. In 2010, Ryan launched Ryan Specialty Group - a brand new wholesale broker. He brought on a star-studded board, crucially including Tim Turner, formerly president of CRC - and Turner brought 120 of CRC’s 800 employees with him. CRC sued in Illinois on the basis of their non-competes, Ryan moved the suit to California, and Ryan won.

Ryan doesn’t have a computer on his desk - because he only needs a phone.

In 2022, Ryan Specialty reported $1.7bn of revenue, up 20% on the previous year. Having IPOed in 2021, it’s now worth over eleven billion dollars.

Looking back over that story, the US insurance broking industry seems dominated by three forces: the centrifugal agent force, expelled by the logic of Dunbar’s number; the ineluctable arithmetic of the private equity rollup; and the giant personalities that pull markets along with them. It’s not just that brokers can take their clients with them when they leave; executives take their brokers with them when they leave. As such, broking makes for a fascinating case study: but it’s not aggregation theory in the mould of Facebook and Google. Instead, all these mergers and divorces constitute a vicious, sharp-elbowed battle for control over indirect customer relationships. Abandoning any hope of going direct, brokerages and their sponsors wage a war for talent. I wonder what Marx would have made of that.