One Up

I originally wrote this essay for my company’s blog, but I think it’s pretty interesting to anyone who’s ever played FarmVille, Angry Birds, or Clash of Clans - the hidden economics are pretty interesting!

Joost van Dreunen's 2018 book One Up is a guide to the business of video games. It distils decades of experience as an industry practitioner and business school professor, but in this article we've picked out three themes of particular interest to people in the business of mobile games: the intertwined nature of creative and commercial success, the value of making your complement a commodity, and the growth of ads as a revenue model. Since van Dreunen's book was published in 2020, it uses 2018 data - so it misses the pandemic, the rise of social casino, and the 2022 tech recession; nonetheless, it's an insightful summary of the past combined with a view of the future that in hindsight holds up well.

Van Dreunen's main thesis is simple. In spite of what people in the industry might like to think, games are big business. As he puts it in the preface, "much of the success in the games industry has been the outcome of an effective exchange between a creative vision and an accompanying business model." As such, it's not possible to understand the story of gaming without understanding the commercial pressures and incentives at play.

For the world of mobile games, one of the most important commercial innovations was the idea of free-to-play games monetised by vanity items. This model had been pioneered Tencent, which built a free social network monetisaed by selling usernames and customisable content. And Tencent would go on to acquire Riot Games, the makers of League of Legends, who intended from their first pitch deck to sell "collectible digital content".

This business model depends on data and analysis; for instance, Zynga's early revenue depended on paid items, and they relentlessly optimised their store accordingly. "In response, many held Zynga in low regard, arguing that instead of publishing true creative experiences, it merely designed its content to funnel players through a never-ending monetisation loop. This approach deviates strongly from the traditional emphasis on creativity and delivering immersive experiences." So Zynga, the most influential games company in the world for a period of time, allowed commercial incentives into its creative process in an almost unprecedented way.

When most people think about games, they think about product - but insiders know that marketing can be even more important. For instance, in 2014 THREES was launched after 14 months of work from two developers. Despite going on to win an Apple Design Award, within 6 days the game had been copied, and the free-to-play clones soon dominated it in the App Store - with Ketchapp's 2048 being just the most successful of the genre. The same thing happened when Lion Studios, a subsidiary of Applovin, rushed out a Wordle app to capitalise on the success of Josh Wardle's viral web app. The marketing resources of big studios are particularly important in today's world, where ad-supported models are dominant.

Another way that commercial models impacted the creative aspect of the gaming experience came in cross-platform titles; the most successful of which was Fortnite, which Epic Games launched on Steam, Xbox, Playstation and mobile all at once; the effectiveness of their bizdev team in getting these partnerships done was vital to their ability to sustain the massive player base necessary to keep lobby waiting times down in Battle Royale games.

As such, van Dreunen argues that "the business behind gaming the games is both a critical component in facilitating and limiting creative processes, and a source of immense strategic advantage when companies develop innovative business models." One of these innovative business models was Supercell's use of a federation of self-sufficient small teams - or cells - each of which is free to fail fast. This still continues today; Ilka Paananen discussed it in this article, and Boom Beach: Frontlines, the latest product from Space Ape, a Supercell subsidiary, will be shuttered this month.

The second key theme in the book is more general. In his 2002 classic Strategy Letter V, Joel Spolsky argued that "All else being equal, demand for a product increases when the prices of its complements decrease... Smart companies try to commoditize their products’ complements.". He was writing to explain why big software companies fund open-source development; but his insight applies to gaming too.

At its peak, Zynga drove roughly one-fifth of Facebook revenue - a genuinely stunning number, given Meta's scale today. Zynga's revenue grew from $19M to $1bn+ between 2008 and 2012, and it was heavily supported by discounted traffic from Facebook. The support Facebook gave to Zynga served to make Facebook's complement - game content that engaged users and drew them to the platform - more attractive to users, growing its own market.

Apple used similar business logic in 2009, when they changed the App Store policies to allow freemium games. In the console era, Microsoft and Sony had subsidised the price of game consoles to charge consumers premium prices for games; the complement was the hardware. But Apple had positioned themselves as a hardware manufacturer first and foremost, and so Spolsky's law dictates that they should make software, their complement, as cheap as possible. By allowing publishers to market free-to-play games with in-app-purchases, Apple executed one of the most commercially successful moves in the history of gaming - perhaps only with the exception of ATT. The abundance of free games from 2009 drove the adoption of the iPhone, which grew from selling 11M units in 2008 to 218M in 2018. On the other hand, they unlocked more profitable business models for games companies, since IAP models provided the prospect for longer-term monetisation.

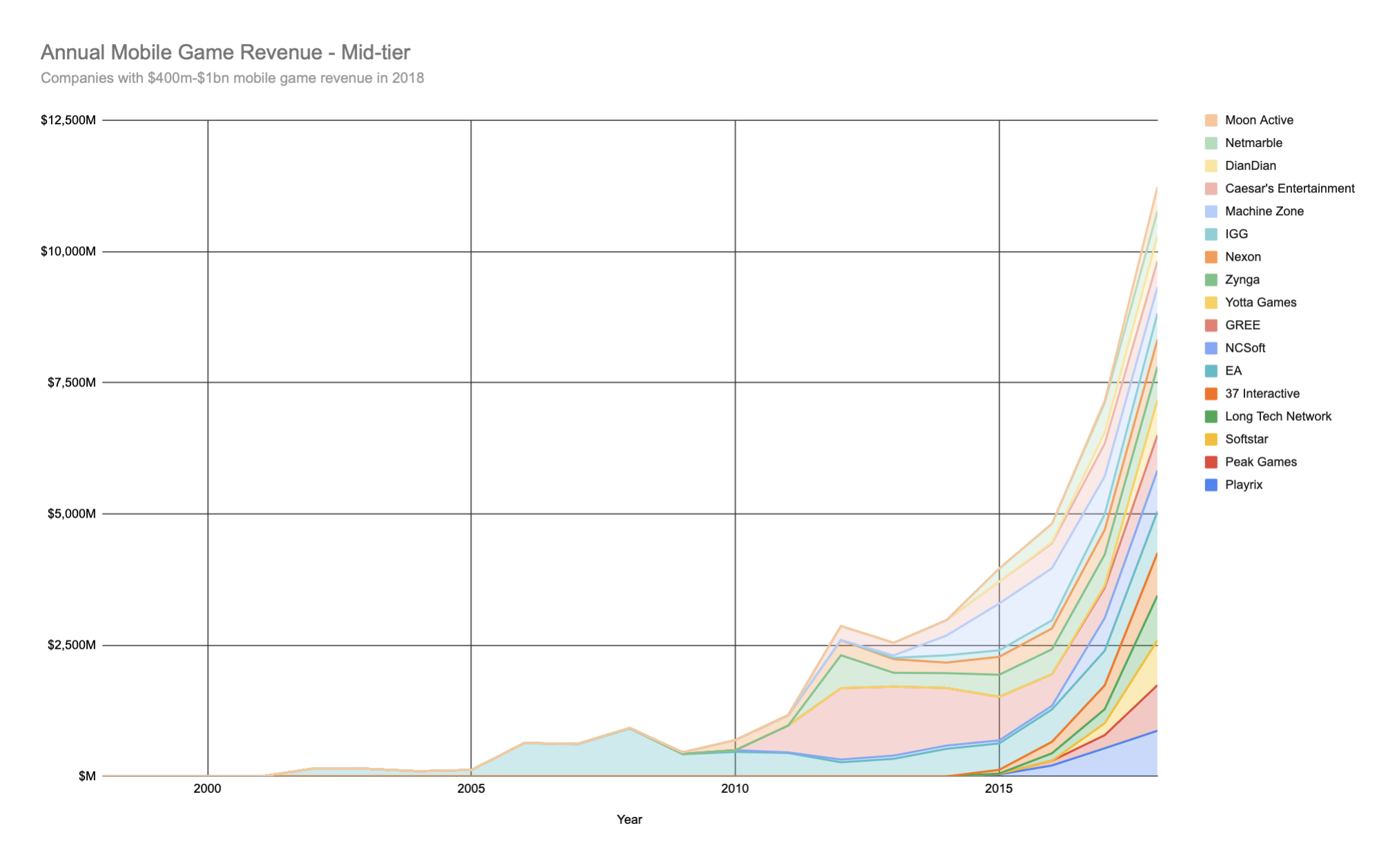

The meteoric growth of mobile gaming revenues; these would go on to increase through the pandemic, before stabilising in 2021/2022. Does 2023 have a recession in store?

This development had several important consequences; first, it created the first "whales" - users who spend thousands of dollars in game. This is an example of demand heterogeneity, a concept which van Dreunen introduced in the context of PC gaming. Some consumers who would never pay $60 for a AAA console game might still spend hundreds of dollars on a freemium game, thus unlocking a new set of customers for publishers to capitalise on. The existence of whales also made possible the social casino titles which flourished during the pandemic; companies like Playtika and Aristocrat depend on these big spenders, in spite of the ethical issues involved. And through it all, Apple still take a 30% cut on IAP revenue, the subject of bitter lawsuits in Europe from Epic Games and Spotify. Last, the long-term nature of freemium revenue models (whose log-linear character we discussed in another post) set the stage for ad-monetised revenue models.

The third theme to highlight from van Dreunen's book is remarkably presicent: his prediction of the growth of online advertising. In his last chapter, van Dreunen identifies two possible future revenue streams: ads and subscriptions. While ad monetisation might seem inevitable in hindsight, "It has been a long-held belief that advertising and video games do not mix. Ad revenue historically has played only a marginal role in interactive entertainment, despite a much greater prominence everywhere else."

Van Dreunen tells the story of Microsoft's failed acquisition of Massive , an early ad network, for $200m in 2006. While Microsoft had hoped to move into gaming and capture a bigger share of audience attention, the gaming industry just wasn't ready for ads. Massive failed to onboard enough publishers because "game developers had never before considered advertising as a relevant revenue stream", and players were similarly unhappy about ads - perhaps justifying the publishers! In general, publishers didn't want to tarnish their cherished franchises by festooning them with ads.

Nonetheless, van Dreunen points out that global ad spend was $650bn in 2018 - with $70bn on TV in the US, $15bn on US print, and $14bn on US radio. Gaming, which was a $40-50bn revenue business in 2018, would do well to capture some of that waterfall of capital. We've already talked about the importance of Facebook's support for Zynga in the early days; it's ironic that Zynga, which was primarily IAP-monetised at it's peak, helped spur the growth of the ad-revenue megalith that Facebook is today. But gaming companies took their time to incorporate ads: in 2013, King were making just 1% of their revenue from ads, which led them to suspend them entirely - only to reverse that decision in 2017.

Note that Zynga did just $18M revenue in 2008 - so overall, there's a steady upwards trend in ad revenue, that continued past the publication of van Dreunen's book.

But the pandemic saw a huge increase in ad revenue for mobile games; as consumers were stuck at home, they turned to their phones for entertainment, and so brands sought them out with ever more aggressive advertisement. That being said, ATT presents a massive challenge for the industry, which Facebook and other ad networks will have to innovate to overcome. Nonetheless, van Dreunen was right to argue that "advertising presents a credible candidate for how interactive entertainment will generate money in the future."

Nonetheless, marketing has become more difficult since the early days of the App Store; van Dreunen presents a shocking graphic showing benchmarked CPI and ARPU trends over an eight-year period. Since 2018, especially with the restrictions on personalisation enforced by Apple's new policies, the gap has only widened, making many fun games unviable - especially those produced by smaller studios.

Waterfull is in the business of helping mobile games companies monetise their games more effectively. If publishers can sell ads more profitably, they'll generate more revenue to spend on their games, without harming the user experience. If advertising can be made as profitable as possible for the publisher, then resources can be channelled to development, ultimately benefiting the consumer. As van Dreunen argues, success is not merely creative - mobile games companies have to optimise their commercial strategies too.