mach

Apparently, it’s brat summer.

Brat summer means a pack of cigs, a Bic lighter and a strappy white top. It means living off Tangfastics and never, ever going to the gym. It means Charli xcx and Chappell Roan.

Sadly, I’ve come to acknowledge that much as I like some of the Charli songs, I am basically the opposite of brat: I don’t smoke, I sometimes go to Barry’s at 7am, and much as I like Tangfastics, I also eat vegetables. In that sense, I feel eminently countercultural.

Everything I know about brat, I learned off Instagram reels and this incredibly helpful Substack. And based on that Substack, as I explained last night in a kitchen in Dalston, I reckon Machiavelli nailed the underlying dynamics of brat way back in the sixteenth century.

mach is brat.

According to Emma Garland:

The brat exercises authority by defying it until they get their arse handed to them, the dom (another foul word) acquires it by finding ways to get them under control.

The dom wants to rule; the brat wants not to obey.

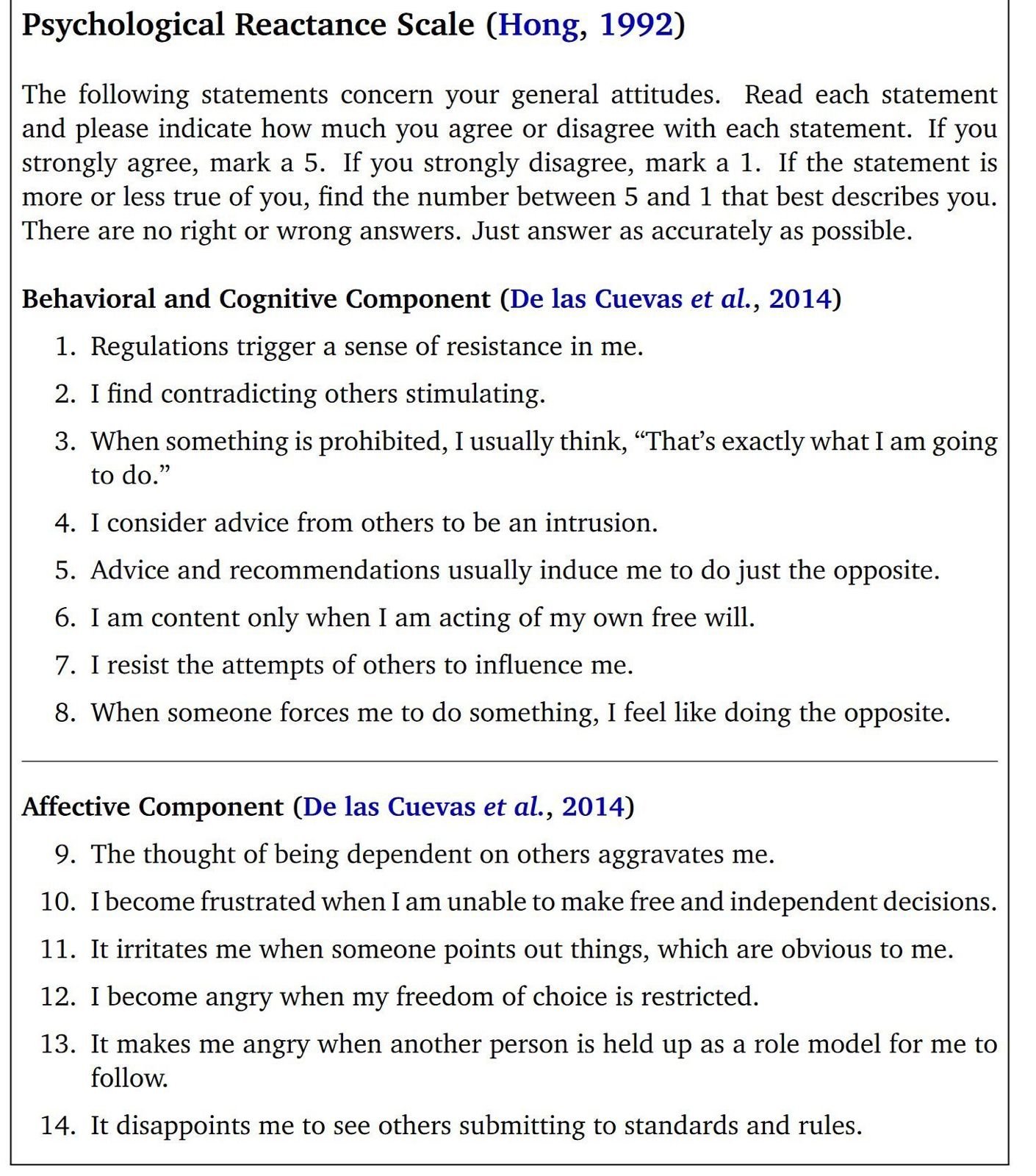

This is, like, a generalisable principle of human nature. You can think about it at the individual level in terms of reactance: some people just hate being told what to do!

But it also applies to groups, and that’s where Machiavelli comes in:

The people do not want to be dominated or oppressed by the nobles, and the nobles want to dominate and oppress the people. And from these two different dispositions there are three possible outcomes in cities: a principality, a republic, or anarchy.- Machiavelli, The Prince, ix

Machiavelli’s idea that there are two dispositions, which he calls umori (or humours) is contra Nietzsche, who argues that everyone, including the people, want to dominate and oppress - that’s the will to power, and it’s the only disposition:

Wherever I found the living, there I found will to power; and even in the will of those who serve I found the will to be master.

Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, The Second Part: On Self-Overcoming

Nietzsche is not brat.

But I actually think Machiavelli has a better take here: not everyone wants to boss other people around. In fact, some people might even like being told what to do; they want to obey; they break the brat/dom binary. One great exposition of this point of view comes from the Grand Inquisitor, Ivan’s story in Dostoevsky’s great novel the Brothers Karamazov:

I tell You, man has no more pressing need than to find someone to whom he can give up that gift of freedom with which he, unhappy being that he is, was endowed at birth.

…

Had You forgotten that peace and even death are dearer to man than freedom of choice in the knowledge of good and evil? Indeed, nothing is more beguiling to man than freedom of conscience, but nothing is more tormenting either.

…

These people are more than ever convinced of their absolute freedom, and yet they themselves have brought their freedom to us and laid it submissively at our feet... For only now has it become possible to contemplate happiness for the first time. Man was created a rebel; surely rebels cannot be happy, can they?

Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, Book V Chapter 5

Man was created a brat; surely brats cannot be happy, can they?

It’s a great line, mocking Rousseau: "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” In contrast, the Grand Inquisitor argues that if you observe that people really want to do as they’re told ,the last thing you should do is try to free them! Dostoevsky most likely agreed more with the Russian socialist revolutionary Alexander Herzen, writing in the 1840s: “Fish were born to fly - but everywhere they swim.”

Dostoevsky, sadly, is not brat.

Garland makes two further great points in her essay. First, she diagnoses the force that really underlies the brat/dom relationship. It’s not will to power - it’s will to win:

“The most realistic answer as to why is also the most obvious: everyone wants to win.

That is a massively overlooked motivation in conversations about sex and dating generally. Or, if not overlooked, then wilfully ignored because it is both obvious and humiliating to admit. Everyone wants to feel desirable. Everyone wants to be the big dawg. At the very least, everyone wants to feel good about themselves. This is the strongest force and the biggest source of conflict within the heterosexual sexual marketplace in the 2020s, because we get that validation from very different places.

One idea this essay is missing - or perhaps which is implicit throughout! - is the great Oscar Wilde quote: "Everything in the world is about sex, except sex. Sex is about power.”

Naively, one might think that Wilde here is supporting Nietzsche’s argument - everything, at its core, is about will to power. But that power doesn’t necessarily take the form of domination, of the will to be master; what Garland brings out is that there are ways to win that don’t involve becoming master, and it’s those ways of winning that Nietzsche - Nietzsche the lonely, Nietzsche the mad, Nietzsche who systematically misunderstands and mischaracterises women - missed. Winning is a more powerful explanation than power.

The uplifting part of Garland’s argument comes at the end:

Bratting is fun because it levels the playing field. It lets everyone win at their own game. It lets women be smart-mouthed and manipulative and it lets men be controlling and punitive. And then it lets you both cave without having to cop to it. No winners, no losers. Only a cycle of power that goes around and around, feeding the irresistible fantasy that anyone has control over anything at all. A brief but mutually beneficial respite from the endless gender wars.

From the two dynamics, brat and dom, we get a healthy synthesis. No winners, no losers, a cycle of conflict that is mutually beneficial. This is the Machiavellian view of the world: conflict, but healthy and productive conflict. But this conflict had to be class conflict: tumulti between umori:

I say that those who condemn the tumults between the nobles and the plebs, appear to me to blame those things that were the chief causes for keeping Rome free, and that they paid more attention to the noises and shouts that arose in those tumults than to the good effects they brought forth, and that they did not consider that in every Republic there are two different viewpoints, that of the People and that of the Nobles; and that all the laws that are made in favor of liberty result from their disunion;”

Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, Book I Chapter IV

In making this argument, Machiavelli disagreed with the Sallustian (Bellum Catilinae, X viii) received wisdom that concordia parvae res crescunt, discordia maximae dilabuntur (by concord, small communities grow, and even the greatest will be destroyed by discord). He had it that class conflict in the early years of Rome was “the primary cause of Roman liberty.”

And suppose someone were to say: the means were extraordinary and almost barbarous. I will respond that every city must possess its own methods for allowing the people to express their ambitions.

Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, Book I Chapter IV

Of course, not all conflict is good. Machiavelli agreed with Guicciardini that factional conflict, characterised by sètte (sects), is destructive. When the conflict is between groups that cut across social classes, perhaps with a Catiline or Clodius (both from ancient patrician families) using the rioting plebs to seize power, the state is endangered:

It is true that some divisions are harmful to republics and some are helpful. Those that are harmful are accompanied by sects and partisans; those that are helpful are maintained without sects and partisans. Thus, since a founder of a republic cannot ensure that there will be no enmities in it, he must at least ensure that there are no sects.

Machiavelli, Florentine Histories, Book VII

Machiavelli is so brat.