Bundling and Unbundling Insurance

One of the “frameworks” that I think about a lot comes from Ben Evans’ 2019 article about SaaS vs spreadsheets:

“There are dozens of companies that remix some combination of lists, tables, charts, tasks, notes, light-weight databases, forms, and some kind of collaboration, chat or information-sharing. All of these things are unbundling and rebundling spreadsheets, email and file shares.”

I think this goes nicely with an idea from a 2021 Matt Levine newsletter:

“A (the?) main move in finance goes like this:

1. You have a risky thing. It will be worth a lot of money in some states of the world and less money in some other states of the world. Perhaps it will be worth $200, or $100, or $50. Perhaps it is trading at $100 now.

2.You divide that risky thing into junior and senior claims. When you find out how much the risky thing is worth, you pay off the senior claims first, and then the junior claims get whatever’s left. Perhaps you issue $50 of senior claims and promise to pay them back $50, and then you issue $50 of junior claims and promise to pay them back whatever’s left. If the thing ends up being worth $200, the senior claims get $50 and the junior claims get $150 and triple their money; if the thing ends up being worth $50, the senior claims get $50 and the junior claims get $0 and lose all their money. The junior claims are extra-risky — more risky than the original risky thing itself — while the senior claims are, in this hypothetical scenario, completely safe. The senior claimants put in $50 and get back $50 no matter what.

There are variations on this move; principally, you can divide the thing into more than two tranches of claim. (Very safe super-senior claims get paid first, quite safe senior claims get paid next, then somewhat risky mezzanine claims, then quite risky equity claims.) Also you can compose this move: You can divide a bunch of things into junior and senior claims, bundle a set of junior or senior claims together, and then slice that bundle into new junior and senior claims.”

So SaaS is about a combining features to build something more or less specific; finance is about slicing up risk. SaaS and finance are different, but I think these framings rhyme.

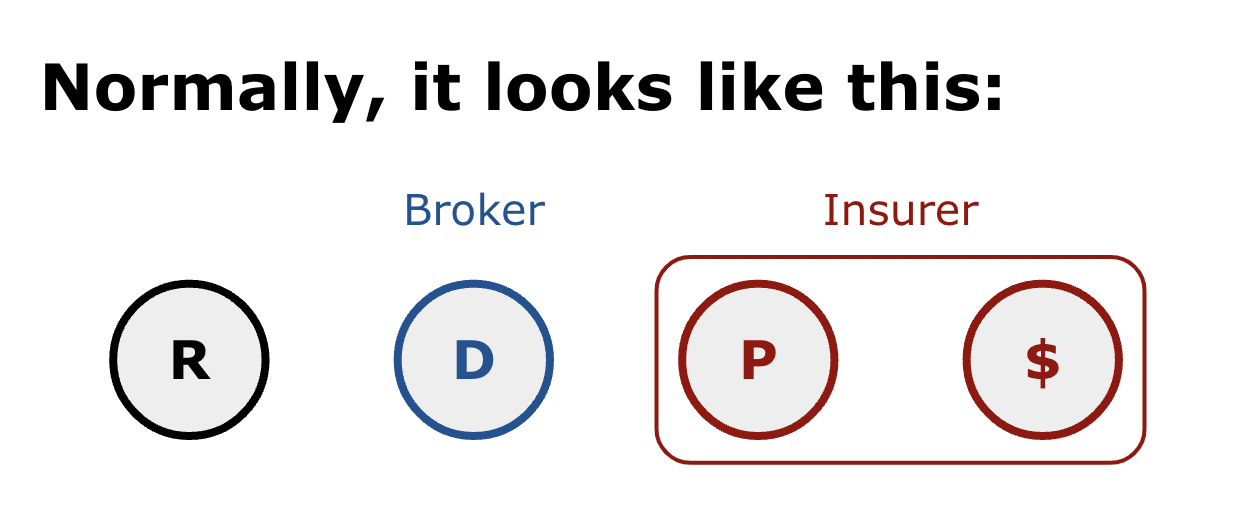

Insurance is a branch of finance, and so it also involves slicing up risk - but that’s only part of it. I think it’s helpful to think about the process of placing insurance into four elements: a risk, distribution, a pricing function, and a balance sheet. You can combine these four elements in fun ways.

A company has a risk that they would like to insure. They speak to an insurance broker. The broker knows lots about risks like this one, and also knows lots of people who can price risk. She introduces the risk to these people, who say something like, “if you pay me £10 today, I will take on the risk that your £1000 building falls down some time in the next twelve months.” And the people pricing risk can do that, because they’ve got a balance sheet to back them up.

In this example, the pricing function and the balance sheet are bundled within a big insurer like AIG, but the distribution is not - it’s handled by a separate firm, a broker like Marsh.

It’s possible to unbundle the pricing function and the balance sheet.

The “pricing function” at AIG is an underwriter, who is a person. That person might want to start their own company. They know their business, and so they have a good pricing function, but they don’t have a balance sheet. Fortunately, people who can underwrite risk can normally find a balance sheet (often from another insurer) that’s happy to give them some money to play with.

So in this case, the ex-AIG underwriter would set up an MGA, or ‘managing general agent’, and call a reinsurance broker to arrange £100m of ‘paper’ from someone with a big balance sheet, like, I don’t know, AIG. That means that the ex-AIG underwriter can use her new MGA to take in up to £100m of insurance premium from risk-holding companies over the next year - and AIG’s balance sheet will cover the risk that those risks generate £110m in claims.

However, the reinsurance broker typically gets paid 2.5% for doing this. The MGA might get paid 10-20% of the £100m as a “management fee”; the MGA will then pay another 10-20% “brokerage” fee to a broker for showing them risks to underwrite; and then the MGA will also take home 20% of any underwriting profit as a “profit commission”. Hedge funds charge 2&20 - MGAs charge 20&20, but the people generously providing them with a balance sheet also pay to get capital in the back door, and get risks in the front door.

Here’s a surprisingly good article about MGAs from McKinsey. One point they make that I agree with - MGAs make most of their money on the ‘managment fees’; the goal is (normally) to write as much premium as possible at a given level of profitability. This is basically how you run a UA team at a mobile games company…

MGAs are a good idea for smart underwriters, because they can focus on what they’re good at - they don’t have worry about building their own balance sheet.

MGAs are a good idea for people with big balance sheets, because they can deploy capital flexibly, deciding year-to-year which (if any) MGAs they want to back. That’s much better than the alternative, which is hiring in a fully-loaded team of underwriters with all their support stuff - much harder to spin up and down as market conditions shift. For example, a balance sheet might decide one year that they want to deploy capital into underwriting terrorism risks in the Gulf, but get out of Texas wind storms; or that one particular wind storm underwriter is doing a bad job, and they’d prefer to back another. This flexibility comes with higher fees, but the market for MGAs is growing steadily.

MGAs are a bad idea for underwriters because they might get their capital pulled from them next year - if they get a bit unlucky with their underwriting, or they have a bad reinsurance broker. It absolutely happens that ostensibly sound MGAs run by reasonably smart underwriters lose their paper, which is very bad news for the MGA.

Shared and Layered

So far, though, we’ve been assuming one risk, one method of distribution, one pricing function, and one balance sheet. The reality, though, is that you can get many of each of them involved in any one transaction.

For example, you might bundle risks together and have an underwriter price them as a cohesive whole - perhaps a portfolio of homes in Texas, or a fleet policy covering damage to the vehicles owned by a trucking firm. But the trucking firm might prefer to buy individual policies on each truck, rather than take out a firm-wide policy. You can also get this in reinsurance, which basically involves the insurer treating insurance policies as risks, and finding people to insure those policies. If you are an insurer and you’ve insured oil rigs owned by Equinor, the Norwegian state oil company, you might buy facultative reinsurance on individual rigs, treaty reinsurance across all your rigs, or (most likely) some complicated combination of both. Side note - facultative reinsurance is so similar to direct (i.e. normal) insurance that brokers talk about “direct and facultative”, or D&F.

You might find that underwriters are backed by more than one balance sheet - an MGA will probably have paper from multiple people.

You might also get a case where an underwriter will say, “you should be paying £10 to insure the risk that your £1000 building falls down some time in the next twelve months; however, I don’t want to take all that risk. So if you pay me £2, I’ll take on 20% of the risk, and you can find other people to take the other 80%”. Typically, other underwriters (i.e. pricing functions), backed by their own balance sheets, will follow the same pricing terms as the “lead” underwriter.

The same underwriter might instead say, “I don’t want to take all that risk. If you pay me £4, I’ll take on the first £200 of losses on your building; find someone else to take on the other £800.” Combining the two gets you a “shared and layered” structure, particularly common in reinsurance deals - where the risk is not a commercial client, but the insurance contracts struck by another insurer.

All this comes together in complicated ways. For example, the risk on Amazon’s North American property portfolio is broked by Willis Towers Watson, one of the biggest broking firms in the world. That risk might be treated as one single entity, but it’s likely that different kinds of property will be treated differently - perhaps datacenters are separate from depots. The risk is shared across more than 60 different balance sheets, with pricing set by many different underwriters, some following and some leading, all shared and layered and reinsured. The complexity this generates - complexity that’s closely related to the slicing that Matt Levine mentions - is why brokers matter, and why knowledge hubs like the City of London are so important for getting deals done.

Here are some example reinsurance towers I found on the internet - what they don’t show is that each layer could be shared between many different reinsurers.

It’s possible to bundle all four elements into one, through what’s known as a captive insurance company. In this context, a big company will set aside part of their balance sheet to cover potential losses, essentially performing the pricing function internally. For example, most energy companies - Exxon, Shell, Chevron - will insure their oil rigs and refineries in the global insurance market. Much like Amazon’s property portfolio, these can be very complicated transactions. But BP famously self-insures - all the risk of an event like, I don’t know, Deepwater Horizon, is covered by their own balance sheet. Entertainingly, this means that every time BP does try to buy insurance for something, the market treats them with deep scepticism - adverse selection is at play!

Lineslips and Binders

In the scenario where an underwriter will price a risk, but only take on a fraction herself, the broker needs to go and find other insurers to come in - and typically, they’ll come in at the same terms or not at all. There’s a lead-follow dynamic, where the terms are set by the leader, and the followers choose whether they want to sign up to them.

However, filling in the follow capacity can be time-consuming for brokers. Given that the risk has already been priced by the lead underwriter (and backed 20% by her balance sheet), nobody else actually needs to do any pricing - all you need to do is find balance sheets to fill in the remaining 80%.

And so one solution is to set up a lineslip, where a group of insurers pre-agree that if a lead underwriter is happy to price a risk that falls within certain parameters, the other insurers will fill in the remaining capacity. Lineslips are arranged by brokers. So Marsh might go to AIG and ten other insurers, and set up a deal whereby if AIG agrees to underwrite a risk, the other ten insurers will always follow at the same terms. AIG get paid for this in various ways - they get better dealflow and may also receive fees. In essence, you’ve got one broker, one pricing function, but multiple balance sheets. Lead underwriters can also arrange follow capacity by themselves, independent of any broker - that’s called a consortium.

Good brokers anticipate underwriter questions; they prepare answers in advance. For instance, if a broker is broking a professional indemnity policy for a law firm, they need to know roughly three things: the firm’s revenue, the number of partners, and the five-year loss history. With that information, a broker will be well-prepared to go to any underwriter, but a really good broker will appreciate the peculiarities of each underwriter they talk to, and prepare answers to the difficult questions they each tend to ask.

And so brokers, who might see more risks than any underwriter, learn not just what the underwriters want to see in a risk, but how to price them. They’ll approach an underwriter with a suggested price - and the underwriter will often agree. The gap between broker and underwriter understanding of pricing gets even smaller when pricing is determined by risk models, since brokers and underwriters use the same models. One underwriter told me recently that he finds it a bit disconcerting when brokers approach him with print-outs from ‘his’ system - because they’ve bought a licence to his company’s modelling software.

If underwriters and brokers can agree on pricing without any negotiation, because they both understand the technical (i.e. model-driven) and contextual (market-driven) aspects of pricing, then why not just let the brokers price the risk themselves? This is called delegated authority: one or more underwriters delegates authority to a broker, letting them “hold the pen” to price a risk on their behalf. Just like with an MGA, this lets a broker charge higher fees - but they'll only be given the authority to write a lot of premium if they do a good job underwriting. The incentive to write more business keeps incentives aligned.

Underwriters delegate authority to brokers they trust, on an annual basis, with a more or less stringent set of underwriting guidelines. These guidelines concern both the type of risks that can be written, and how they should be priced; the particular authority being delegated is called “binding authority” (binding being the word for formalising a contract of insurance), and hence delegated authority agreements are often known as binders; sometimes they’re also called facilities.

Binders tend to be backed by many different insurers; typically, though, one or two will act as leaders, responsible for making sure that the broker is staying on the straight and narrow. In that sense, they look very similar to lineslips; both are arranged by a broker, but in a binder, the broker does all the underwriting themselves.

And so, through a fairly logical series of arrangements, pricing is unbundled from the balance sheet and bundled with distribution.

What else?

Big companies tend to hire former brokers as in-house risk managers (Alison Quinlivan does this at Google); insurance companies will have reinsurance buyers that serve an analogous function further down the value chain. Sometimes these people will set up captives (which in the case of a reinsurance buyer, just means buying less reinsurance); one might assume that they could just do the broking themselves. However, in practice, any company which can justify a full-time risk manager has complicated enough insurance needs that they still need brokers; and hence it’s very difficult to bundle risk and distribution unless you’re doing a BP-style captive.

The other option is to bundle distribution, pricing and balance sheets; in essence, for insurers to go “direct” to customers. This is pretty common in personal lines; you might buy life insurance directly from Aviva without going through a broker. But that’s partly because the product itself is commoditised - you don’t need uniquely personalised life or health or car insurance - and hence easy for consumers to compare different providers. This is made particularly easy in the UK by the four big price comparison websites - CompareTheMarket, MoneySupermarket, GoCompare and Confused.com. But when insurance gets more complicated - and commercial insurance is complicated - it’s much harder to generate like-for-like comparisons, and the marginal cost of generating a quote goes way up. It seems that there’s always going to be a place for a broker - a professional agent that can advise clients. As tech improves, sourcing and generating quotes - the side of the distribution that interfaces with the pricing function - will get easier. But we’ll always need brokers.